roscoe mitchell | old quartet & solo saxophone concerts

OLD QUARTET (Nessa 5)

Roscoe Mitchell / reeds, flute, etc., Lester Bowie / trumpet, flugelhorn, etc., Malachi Favors / bass, etc., Phillip Wilson / drums.

Recorded: May 18, 19 and November 25, 1967.

SOLO SAXOPHONE CONCERTS (Sackville 2006)

Roscoe Mitchell / saxophones.

Recorded: October 22 and November 2, 1973 and July 12, 1974.

The music that happened in Chicago in the latter half of the Sixties brought to the fore and consolidated certain trends already inherent (but not yet given full expression) in the “free” music that preceded it. By 1965, certainly, the idea of an unbound and completely collective musical statement had been accepted by many younger musicians as an ideal toward which to work. But for the most part, this remained only an aesthetic postulate.

The most significant bands of the period – Coleman’s, Coltrane’s, Taylor’s, Ayler’s, Shepp’s, and others – were largely built around single musicians with highly personal artistic concepts. The bands were collective, but perhaps mainly in the sense that the “rhythm sections” had been freed from their strict time-keeping roles and were now free not only to comment on statements by “soloists” but even (in some cases) to share an equal explorative space with them. But though someone like Taylor or Ayler (or Sunny Murray) might “break up” their improvisations in an extremely fragmented and non-linear manner, these still generally occurred within essentially forward-moving structures, ones which – though they were well beyond any kind of song form – could still be felt to be proceeding logically (in a line) from one point to another. In this sense, the aesthetic constructs implied a more linear approach to music than that espoused in practice by the creators who worked within them (who in fact were putting forth both linear and non-linear ideas).

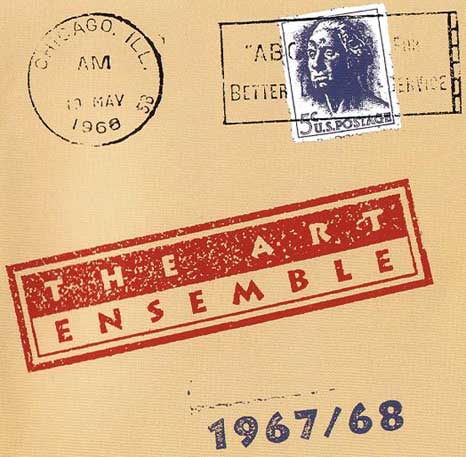

The music of the Chicagoans was different (and, in a certain sense, inevitable) in that it stretched out and formalized a process of creation already implicit in the explorations of the music’s most important improvisers; so that the process itself became as fragmented as the statements it enclosed. (Only Sun Ra, in an orchestral setting, had previously approached this.) In the case of Mitchell, Bowie, Favors, et al. (the Art Ensemble of Chicago), this new found freedom of procedural choice (to move linearly or non-linearly or somewhere in between) was coupled with a freedom of stylistic choice, which enabled them (in so far as it was possible) to encompass and contain virtually the entire history of black music.

In addition, the ensemble’s fascination with tone color led to the incorporation into their music of numerous “little instruments”. These served not only as an extension of their “primary” instruments but to simulate multiple levels of musical activity happening at once. All of the above combined to produce a music with a flexibility and complexity of form (real and sometimes only imagined) not previously attained in an improvisational context.

In Old Quartet, we have the opportunity to look at this process in something of an embryonic state. In “Quartet,” the most ambitious piece – and completely improvised – the above formulations are apparent but have not yet been realized to the extent they would be later – for example, on Lester Bowie’s “Number One” (Nessa 1). The problem is that too much of what occurs seems only tentative and probing rather than necessary; or, to put it another way, the various moments of the piece fall together without too much sense that they had to be connected. Parts of the piece turn out to be of greater interest than the piece as a whole; what we get is some fine work from Lester Bowie and also from Phillip Wilson, both of whom charge the music with energy to keep it moving along.

This is the first recording we’ve had of Wilson with the group, and he proves to be highly sensitive to the players’ needs, always allowing (as they do) the music to find its own context rather than arbitrarily imposing his own upon it. When he finally does truly assert himself (midway into “Part Two”) it turns out to be the right choice, as he paves the way for the piece’s rollicking finish. Hard too to imagine “Old” without Wilson who (along with some fantastic work “up front” from the rest) gives it just the proper down-home seasoning.

“Solo,” the final piece on Old Quartet, is Mitchell working alone, experimenting, attempting to incorporate the principles of the ensemble into his personal aesthetic. Though it is not the alto tour-de-force of “tkhke” (recorded four months later, Congliptious, Nessa 2), it is a fair success on its own terms – surprisingly so as in the space of five and a half minutes Mitchell plays alto saxophone and clarinet, chimes, cymbal, harmonica, and a couple of other percussion instruments. Working mainly with a single motif, the sounds are well integrated (adding texture and color rather than density), yet there is no expectation of what is to come.

On Solo Saxophone Concerts, we get an even better chance to see how Mitchell’s music works. And it works mainly through contrast – of rhythm, pitch, or timbre, applied variously to phrases, motifs, or frequently just single notes. Alto saxophone still seems to be the instrument on which Mitchell has the greatest facility and range and on which he generates the greatest intensity. (Hear, for example, both versions of “Nonaah” and “Ttum.”)

Yet his work on the remaining reeds is not negligible. His soprano work (”Jibbana“) is particularly thoughtful, and he even manages to turn the cumbersome bass sax to expressive ends (”Tutankhamen“). For one piece (”Oobina“) he combines soprano and bass sax, blowing them together and separately, emphasizing again the underlying disparate nature of his art. Solo, then, is a fine musical experience, a somewhat more finished presentation than that of the ensemble on Old; but Old is of great interest, if only for its partial illumination of this group’s early history.

Henry Kuntz, 1975

selected Roscoe Mitchell recordings

Roscoe Mitchell biography:

Roscoe Mitchell (b. August 3, 1940 in Chicago, Illinois) is an African American composer and jazz instrumentalist, mostly known for being “a technically superb — if idiosyncratic — saxophonist.” He has been called “one of the key figures” in avant-garde jazz who has been “at the forefront of modern music” for the past thirty years. He continues “to be a major figure.” He has even been called a “super musician” and the New York Times has mentioned that he “qualifies as an iconoclast.”

Mitchell grew up in the Chicago, Illinois area where he played saxophone and clarinet at around age twelve. His family was always involved in music with many different styles playing in the house when he was a child as well as having a secular music background. His brother, Norman, in particular was the one who introduced Mitchell to jazz. While attending Inglewood High School in Chicago, he furthered his study of the clarinet. In the 1950s, he joined the United States Army, during which time he was stationed in Heidelberg, Germany and played in a band with fellow saxophonists Albert Ayler and Rubin Cooper, the later of which Mitchell commented “took me under his wing and taught me a lot of stuff.”

He also studied under the first clarinetist of the Heidelberg Symphony while in Germany. Mitchell returned to the United States in the early 1960s, relocated to the Chicago area, and performed in a band with Wilson Junior College undergraduates Malachi Favors (bass), Joseph Jarman, Henry Threadgill, and Anthony Braxton (all saxophonists). Mitchell also studied with Muhal Richard Abrams and played in his band, the Muhal Richard Abrams’ Experimental Band, starting in 1961.

In 1965, Mitchell was one of the first members of the non-profit organization Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) along with Jodie Christian (piano), Steve McCall (drums), and Phil Cohran (composer). The following year, the augmented AACM of Mitchell, Lester Bowie (trumpet), Kalaparusha Maurice McIntyre (tenor saxophone), Favors, Lester Lashley (trombone), and Alvin Fiedler (drums), recorded their first studio album, Sound. The album was “a departure from the more extroverted work of the New York-based free jazz players” due in part to the band recording with “unorthodox devices” such as toys and bicycle horns.

The group went through changes again in 1967 and 1969, both in name (changing first to the Roscoe Mitchell Art Ensemble, then the Art Ensemble, and finally the Art Ensemble of Chicago) and the players (inclusion of Phillip Wilson on drums for short span before he joined Paul Butterfield’s band). This group and its incarnations would be regarded as becoming “possibly the most highly acclaimed jazz band” in the 1970s and 1980s.The group lived and performed in Europe from 1969 to 1971, though they arrived without any percussionist after Wilson left. To fill the void, Mitchell commented that they “evolved into doing percussion ourselves.” The band did eventually get a percussionist, Don Moye, who Mitchell had played with before and was living in Europe at that time. For performances, the band often wore brilliant African costumes and painted their faces.

Mitchell and the others returned to the States in 1971. After having been back in Chicago for three years, Mitchell then established the Creative Arts Collective (CAC) in 1974 that had a similar musical aesthetic to the AACM. The group was based in East Lansing, Michigan and frequently used the facilities at the University of Michigan. Mitchell also formed the Sound Ensemble in the early 1970s, an “outgrowth of the CAC” in his words, that consisted mainly of Mitchell, Hugh Ragin, Jaribu Shahid, Tani Tabbal, and Spencer Barefield.

In the 1990s, Mitchell started to experiment in classical music with such composers/artists such as Pauline Oliveros, Thomas Buckner, and Borah Bergman, the latter two of which formed a popular trio with Mitchell called Trio Space. Buckener also was part of another group with Mitchell and Gerald Oshita called Space in the late 1990s. He then conceived the Note Factory in 1992 with various old and new collaborators as another evolution of the Sound Ensemble. He currently lives in the area of Madison, Wisconsin and has been performing with a re-assembled Art Ensemble of Chicago. In 1999, the band was hit hard with the death of Bowie, but Mitchell fought off the urge to recast his position in the group, stating simply “You can’t do that” in an interview with Allaboutjazz.com editor-in-chief Fred Jung. The band continued on despite the loss.

Leave a Reply